Procedure and modalities

All psychoanalysis begins with “preliminary interviews” that serve to identify the analysand’s problems and question his desire to undertake analytical work. These interviews can last from a few days to several weeks. In the course of a treatment, the analysand is usually invited to lie down on the couch, as soon as he no longer needs visual support to talk, when the practitioner is put by the patient in a position to “know something” about the cause of his suffering. Indeed, this situation is a sign of the setting up of the “transference”, one of the hinges of the analytic work. By imagining that the other knows what he suffers from, the analysand transfers his affects onto him; those that he used to reserve for his parents as well as those that constitute his “window on the world”, his fantasy frame. Naturally, the analyst’s role is also to refer the patient to his real interlocutor, whether this is a familiar or parental figure, an abstract or non-existent other, or – more often than one might think – the analysand himself…

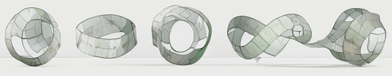

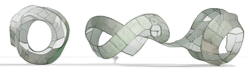

Many contemporary “therapeutic” practices claim that a patient must be reassured by an unchanging framework: a shrink who is always the same, sessions of fixed duration. The Lacanian approach to psychoanalysis, on the other hand, privileges the surprise effect in the encounter. A floating attention is set up in order to feed the questioning of the analysand, in the movement between a “What do you want from me?” and a “What do I want?”, hinge of the desire and its impasses. By questioning the desire of the other and by making assumptions, the patient reveals his own fantasies and desires which can then be analyzed.

A session usually ends when the patient has stated a word, an idea that crystallizes his problem. Occasionally, these “scans” may punctuate sessions in unexpected ways to serve as an indicator of the appearance of a significant element. Also, not obsessed by the regularity of the rhythm of the sessions, the number of meetings can be adapted to the analysand who is not doing well.

A more “therapeutic” approach of analytical orientation will not change much from a psychoanalytical approach, both being punctuated by the vagaries of speech and language in their fundamental knotting to the expression of the symptom. Nevertheless, it seems important to us, particularly in the contemporary societal context, to provide another type of support to people who place a particular importance on the brevity or effectiveness of a more conversational approach, organized around a more direct, face-to-face encounter. Without being put aside, the couch will no longer have a central place here, even if it can be called upon each time its use seems relevant.

The “transference” between patient and therapist will remain an essential hinge of the work. The person in demand transfers his affects on the therapist who will be able to give them back to him in the form of a “reversed image”, a preliminary step to the work of deciphering the symptom in the discourse. The role of the therapist will be there also to refer the patient to his real interlocutor, from the parental figure to the uneasiness produced by his own subjectivity, often denied or repressed.

As in psychoanalysis, a session generally ends when the patient has stated a word, an idea that crystallizes his problematic. These “scans” constitute the possibility of punctuating the sessions in unexpected ways to serve as an indicator of the appearance of a significant element. Similarly, the regularity and pace of the sessions can be tailored to the needs of the patient.

During the first conversation, we look at what the problem is (which is not always obvious) and if my way of working (with psychoanalysis) can suit you (without it being clear in advance in which direction the work will take us). It is also at this time that we make practical arrangements regarding payment and timing of sessions.

In terms of language, I have experience in French (my usual language), English, Dutch (my mother tongue) and Italian.